Building the Parental Bond Through Reading

One prison reading program is fostering connection between incarcerated parents and their children.

Joy Haenlein has always been a passionate advocate for literacy. Her interest in using reading to improve family connections led her to volunteer with CLICC (Connecting through Literacy: Incarcerated Parents, their Children and Caregivers), a New Haven-based nonprofit that uses books and mentors to foster communication between incarcerated parents and their children. “When I started volunteering in 2009, we ran a test pilot program through Danbury Federal Prison with a handful of incarcerated mothers,” Haenlein said. “We found the experience was positive and helped parents learn more about their kids.”

Since then, CLICC’s program has expanded to seven prisons across Connecticut, and Haenlein has grown from volunteer to the organization’s executive director. CLICC also developed a specially-designed curriculum in partnership with Columbia University’s Teachers College. “Children of incarcerated parents often experience stigma, shame, stress, trauma and social isolation,” Haenlein says. “We train our mentors to use books, characters, settings and plots, to explore relationships between parents and kids.”

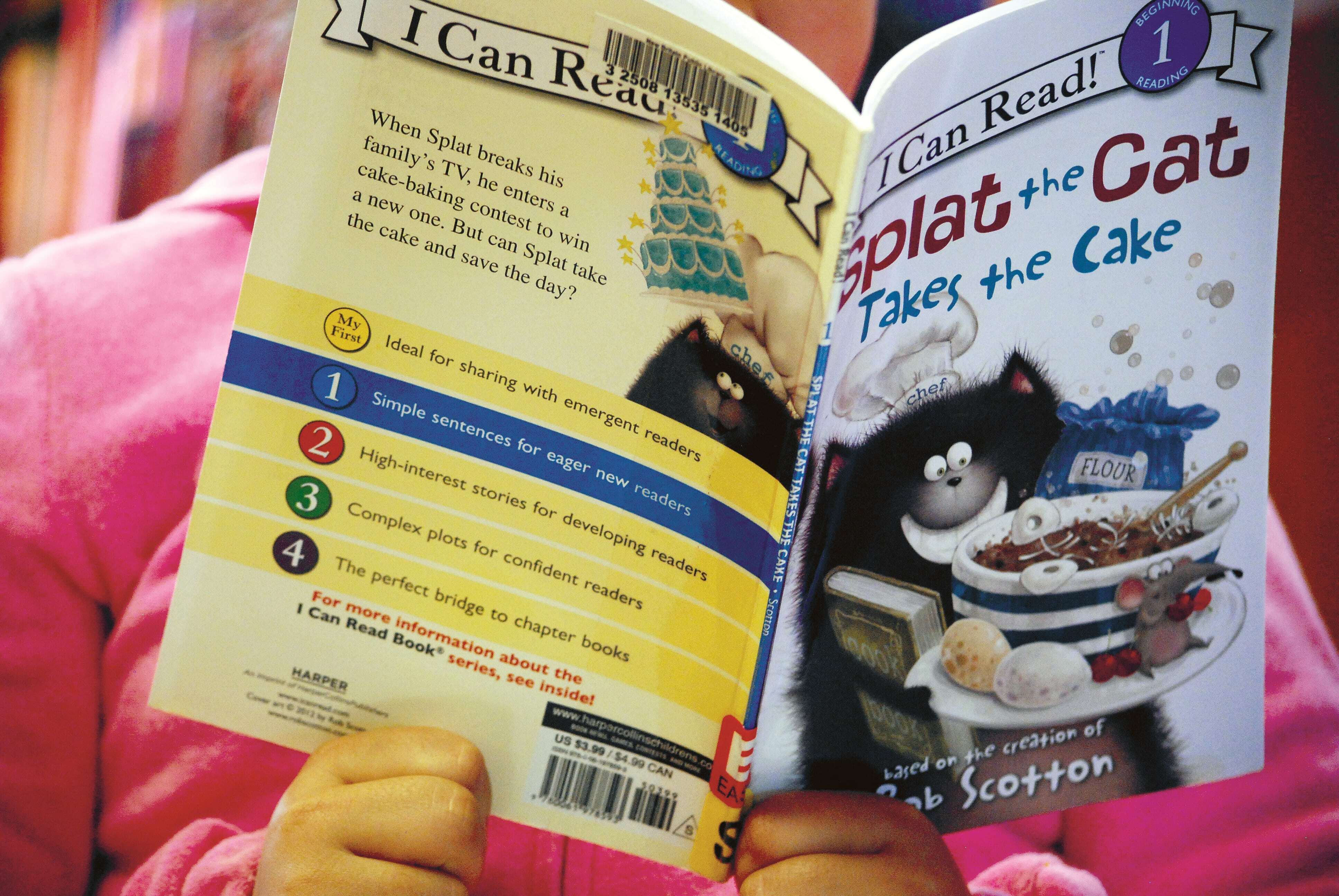

Children select the books that they and their parents both read and discuss through in-person meetings, video chats, letters and phone calls. The meetings and interactions are among the key metrics that CLICC tracks to measure impact. “That [increased communication] helps to create deeper conversations and strengthen bonds between parent and child,” Haenlein says. “Research has shown that both literacy and stronger family relationships help reduce recidivism rates.”

General operations funding from the Community Foundation — $70,000 over two years — has been vitally important to the program’s growth and impact. “We have used those funds to purchase books and to fund training for our youth mentors,” Haenlein says. Many of the youth mentors are college students — including several from Yale’s Undergraduate Prison Project. “Having college students mentoring our kids, especially our high school-aged youth, is particularly important because it feels like a peer.” The mentoring component, Haenlein says, has shown to help children process the emotional struggle of having an incarcerated parent. And, she adds, the youth are becoming better readers.

The parents also benefit from having mentors. Through weekly group sessions they talk about their parenting challenges and concerns. “Oftentimes, we see a lot of peer-to-peer mentoring from the incarcerated parents who share their own experiences and try to help each other.” CLICC also helps parents prepare for their release dates by connecting them to employment and family support services. But the biggest benefit is the stronger family relationships and connections. “Better relationships with their children can provide a stronger social safety net,” Haenlein says, “and better connection to community.”

What inspires you?

Creating a charitable fund makes a difference now and forever.